Timothy Cain has turned his humble YouTube channel into a virtual learning tree where viewers can hear stories and advice from one of the pioneers of modern role-playing video games. Cain’s resume includes being one of the original creators of the Fallout series, Arcanum, Vampire: The Masquerade – Bloodlines, and more.

In a recent video, he discussed how he watched the Internet rise out of Usenet and transform from a scientific and academic platform into a commercialized universe of influencers, misinformation, and bots. He observed that the oldest and youngest Internet users are often fooled by different aspects of today’s digital culture.

I can’t disagree with Cain on his points. The Internet is not real life, even though billions of real people are constantly connected to it. It is muddled by artificially generated content inflated by swarms of bots pretending to be real people.

Dishonest Influence Campaigns

There are numerous examples in recent history of data mining and engineered falsehoods leading to real-world consequences. In some cases, businesses profited heavily from knowingly spreading false information to steer public opinion in a particular direction.

The Cambridge Analytica Scandal of 2016 highlighted how companies leverage large datasets from social networks like Facebook to target individuals with ads designed to manipulate their political opinions.

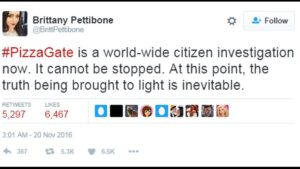

The “Pizzagate” conspiracy (also 2016) spread manipulated content believed to be leaked emails from political figures that indicated there was a pedophile ring operating out of the basement of a pizza restaurant. This conspiracy convinced so many people that the conspiracy was real that one of them brought a loaded gun into the pizza restaurant and opened fire, demanding that the children be released. The only problem is that the restaurant not only wasn’t a front for a pedophile ring, but it didn’t even have a basement.

Social media was rife with disinformation during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. False cures, conspiracy theories, and other fabrications confused the general population with genuine consequences to people’s health and well-being. Theorists put forward baseless accusations that the virus came from Canadian laboratories, was engineered to target specific ethnic groups and more. One widely held belief is that political figures planned the pandemic to sway elections.

Influencers and the Illusion of Perfect Lives

Social media influencers, particularly those who participate primarily in video and photo mediums, are paid based on their ability to influence their audience to buy various products or services. It’s in the name of the profession.

Influencers benefit from presenting their audiences with an aspirational impression of their lives. Their homes are often well-kept and rarely appear lived-in. Clothing, hair, makeup, lighting, and audio are all in place wherever they are and whatever they’re doing. Even the influencers that lean toward a more “chaotic mom life” vibe have their act together enough to spend time on camera telling a wild story with excellent comedic timing every day.

They live lives filled with crazy moments that happen regularly to them, and those moments coincidentally occur in combination with trends that sweep through social media at the time.

This leads the audience to one end: selling products and services. Influencers often have their brands of makeup, clothing, etc., that they pitch as part of what makes them look and feel great.

Bots and Manipulated Engagement

The Internet has more bots than ever, thanks to machine learning and the rise of artificial intelligence (AI). Creating a swarm of bots using a digital bot farm enables an entity to create the illusion of popularity or consensus on various platforms, from Facebook to YouTube.

A YouTube video that typically receives a few hundred views and comments can become a statistical viral sensation with the help of a large enough bot swarm. Leveraging AI tools like ChatGPT, those bots can leave believable and relative comments that are unique and difficult to discern from human interactions.

In our examples of real-world influence campaigns, we touched on Cambridge Analytica. One of Cambridge Analytica’s tools for influencing people was using bots to make the opinions it expressed appear part of a widespread consensus. If a post claimed that Hillary Clinton was eating children and 3,000 comments seemed to agree with it, the reader would be more likely to take the claim at face value.

Clickbait Headlines and the Spread of Misinformation

Perhaps the most noticeable examples of misinformation online are the clickbait headlines that appear on virtually every sponsored post. Articles with titles like “You wouldn’t believe what Taylor Swift drives ” or “This one weird trick saved her millions” are rampant on the Internet. Why? Because they work!

When commercial content farms discovered they could generate nonsense articles with specific celebrity names and give them titles that made the reader believe that they could find some secret or juicy gossip, that was the end of what little sense the Internet had.

Conclusion

The Internet isn’t real. Unless you know the person on the other side of your comment thread, on X or YouTube, the default assumption should be that the person isn’t necessarily human. While it’s on us to be civil to our fellow man, taking the information and emotions of their interactions to heart isn’t advisable.